by Elodie Gavrilof

The Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, which has persisted since the collapse of the USSR, has led to a profound redefinition of “the Other,” dehumanized and manifested, for example, in the war crimes committed by both sides since 1991. The ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023 tragically illustrates the persistence of these mechanisms. This deeply hated “Other” did not emerge from the fall of the USSR but is rooted in conflicts dating back to the formation of nations.

From the start of the Soviet era, authorities justified internal borders through manufactured ethnogenesis. These artificial constructs were revived in 1988 with claims over Nagorno-Karabakh, legitimising the expulsion of the Other—deemed illegitimate on these lands. In 1993–1994, Armenians expelled Azerbaijani populations; the Aliyev governments then weaponized these refugees to forge a national identity rooted in anti-Armenian hatred. Conversely, in the Armenian narrative, Azerbaijan supposedly didn’t exist before 1918. But while the state may not have existed, its people certainly did. The Other is stripped of any historical depth. This deep-seated animosity doesn’t derail current negotiations, but it poses a profound societal challenge that will eventually need reckoning.

The Historical Roots of Hatred: From Empire’s End to Soviet Beginnings

By the turn of the 20th century, Baku had become an industrial city thanks to oil exploitation. It then had around 140,000 inhabitants, of whom 35% were Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians, 21% Transcaucasian Tatars (as they were called at the time), and 19% Armenians (1903 census)1Census of the city of Baku, 1903. Azerbaijani National Archives. Reproduced by MAMMADOVA Shalala. “Armenian-Muslim massacres of 1905-1906 through the eyes of contemporaries”. Baku Research Institute. 2024. Link to the article. Interethnic tensions must be understood in the context of the 1905 Russian Revolution, as well as in the treatment of local workers. Because of their history, Armenians had long been active in the industrial and commercial sectors. Muslim citizens, on the other hand, faced various forms of discrimination from Russian authorities, who regarded Muslim and nomadic populations as “culturally backward”2This is the term used by the authorities. As a result, no Azeri held any important position within the Caucasus viceroyalty, which fueled much resentment. Armenians, much like Jews in Europe, were quickly accused of “getting rich” at the expense of Muslims and became the target of conspiracy theories accusing them of provoking instability in the region. In February 1905, clashes broke out in Baku between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, spreading across the Caucasus, particularly to Nakhichevan and Shushi, and continued until 1907.

In 1918, in the aftermath of the genocide in the Ottoman Empire, many Armenians fled to the Caucasus. When Armenia declared its independence, roughly one-third of its population consisted of war refugees. Around the same time, Stepan Shaumian, appointed by Lenin, established the Baku Commune to lead the revolution in the region. The Commune controlled the city for several months, prompting the Ottomans to send the so-called “Army of Islam,” led by Enver Pasha, to “liberate the city from the Bolshevik yoke.” Though essentially a conflict between the Ottomans and the Bolsheviks, it took shape on the ground as fighting between Turkish and Armenian forces—deepening the already entrenched animosities. This army, commanded by Enver Pasha—one of the chief architects of the genocide—operated in a Caucasus already devastated by the wars of independence of 1918.

The Turkish troops advanced into Armenia, and the descendants of Geghard’s inhabitants recount how their ancestors hid for days in caves around the monastery to survive. This was the first manifestation of “bir millet, iki devlet” (“one people, two States”), a poem written in 1991 by Bakhtiyar Vahabzade. Today, the figure of Enver Pasha is instrumentalized through a political communication technique widely used among far-right movements around the world: the dogwhistle. A dogwhistle is a political communication strategy that uses coded or ambiguous language to convey an implicit message to a target audience while remaining vague enough to avoid direct criticism. For example, on September 18, 2025, the Azerbaijani Embassy in Turkey organized a conference at the Chamber of Commerce in Ankara on “The Army of Islam and Enver Pasha,” the very army that marched on Baku in 1918. The figure of Enver Pasha has also been repeatedly invoked by Turkish authorities, notably in the speech delivered by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Baku during the military parade of December 10, 2020, where he declared:

“Today is a day when the soul of Azerbaijan’s national poet, the great fighter Ahmed Javad bey, rejoices. Today is a day when the souls of Nuri Pasha, Enver Pasha, and the brave soldiers of the Islamic Army of the Caucasus rejoice. Today is a day when the soul of Mubariz Ibrahimov, the commander of Azerbaijan’s martyrs, rejoices. Today is a day of victory and pride for all of us, for the entire Turkic world.”

Depicting Enver Pasha as the liberator of Baku raises serious issues. It reflects the broader pattern of revisionism at play, but it also reveals the subtlety of this manipulation. It acts as a kind of dog whistle: the surface message—a celebration of Turkish-Azerbaijani unity—is embodied in a warlord responsible for orchestrating the extermination of the Armenians.

Rebuilding Hatred After 2020: Shifting Narratives

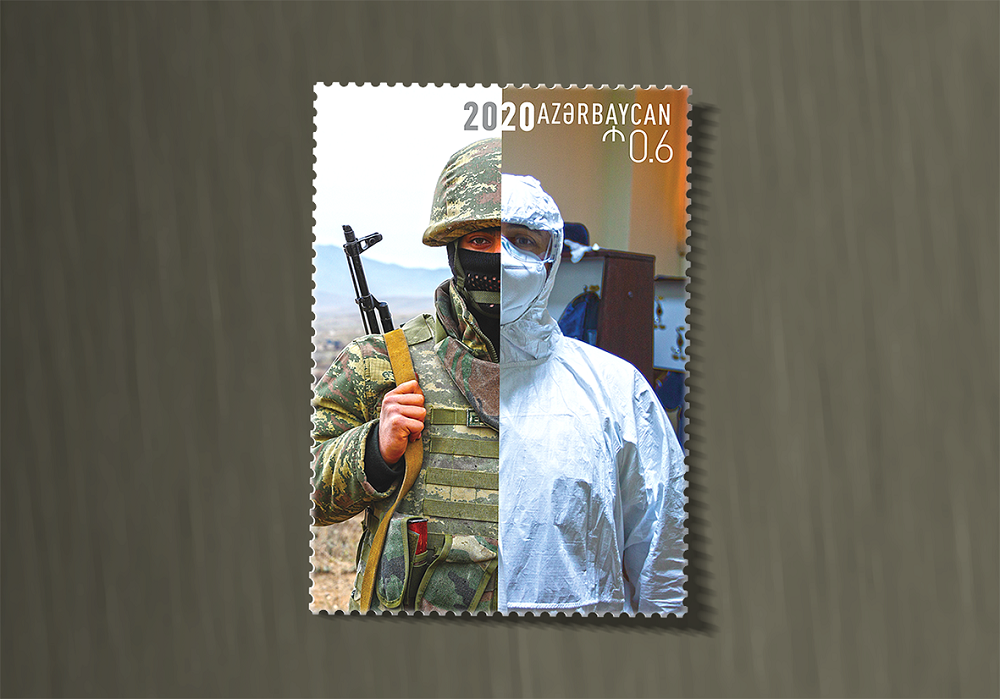

After Azerbaijan’s victory in 2020, some might have expected these narratives to fade. But that didn’t happen. Within months, the authorities opened a “Victory Museum,” displaying wax figures of Armenian soldiers caricatured in grotesque and dehumanizing ways—recycling all the familiar tropes of enemy imagery. Postage stamps were issued depicting Karabakh being “cleansed” with a power washer, as if Armenians were a contagion to be wiped out—an unsettling echo of the COVID-19 pandemic then sweeping the world. No efforts were made to promote dialogue between communities. On the contrary, those who tried—like Bahruz Samadov—were imprisoned. From 2021 onward, Armenians were gradually erased from official narratives.

After 2020, this erasure of Armenians took place not only in space but also in time, through the reinforcement of the narrative about the Caucasian Albanians. The Caucasian Albanians were an ancient people whose church gradually became Armenianised in the early Middle Ages. The Udi community, which considers itself their descendants, is now being instrumentalised to promote a narrative claiming that Armenians are not indigenous to the region. This narrative, too, is rooted in older identity constructions. As early as the 1950s, Azerbaijani historian and orientalist Ziya Buniatov worked on the Caucasian Albanians narrative. His work was, for instance, the subject of Sara Crombach’s doctoral thesis, published in 20233CROMBACH Sara. Myth-making and Nation-Building. Ziia Buniiatov and the Construction of the Azerbaijani Past. Amsterdam : Pegasus. (258 p.). The creation of these narratives aimed at erasing the Armenian presence, both temporally and spatially, demonstrates that beyond economic issues, societies remain far from reconciled, and even further from genuine peace.

All indicators and observers confirm that this hatred, far from subsiding, is growing stronger, just like authoritarianism in Azerbaijan. The image of the Armenian as the ultimate enemy, one of the cornerstones of state-building since the end of the Soviet Union, continues to exist and even to be transmitted. In schools, as shown by the ongoing research of Naira Sahakyan and Lilit Ghazaryan, Armenians are prominently featured but depicted in extremely pejorative ways. As early as 2022, deeply troubling videos were recorded in Azerbaijani schools showing children singing songs of hatred during Victory Day commemorations on November 8. These various signs indicate that this hatred is not only intensifying but also being passed on to future generations.

On the Armenian side, the figure of the “Other” is addressed in a more indirect way. Azerbaijanis are largely absent from public narratives. In schools, there are no courses on Azerbaijan or its people, and this lack of knowledge fosters not only ignorance but also the creation of partially—or entirely—distorted stories. This absence leaves room for misrepresentations to take hold, even if it isn’t the result of a deliberate state policy. The alliance with Turkey, reinforced by the linguistic proximity between the two nations, deepens the confusion and feeds an entangled memory—one that continues to be expressed through the familiar Turkish-Azerbaijani saying, “one people, two states.” The challenge of confronting hatred and rethinking narratives about the Other will remain a central issue in Armenian-Azerbaijani relations for years to come.