In recent years—particularly since 2020—the issue of place names in Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia has become a target of nationalist agendas. Both online and in certain diplomatic circles, the use of place names has turned highly political. Artsakh, Shushi, Shusha, West Azerbaijan, Stepanakert, Khankendi… each of these names, when spoken, reveals the allegiance of the speaker. The act of naming places becomes a tool for communities to assert historical claims over disputed territories. Yet this instrumentalisation conceals a more complex reality: in the 19th century, many of these towns and villages were known by several names, depending on the languages spoken in the area.

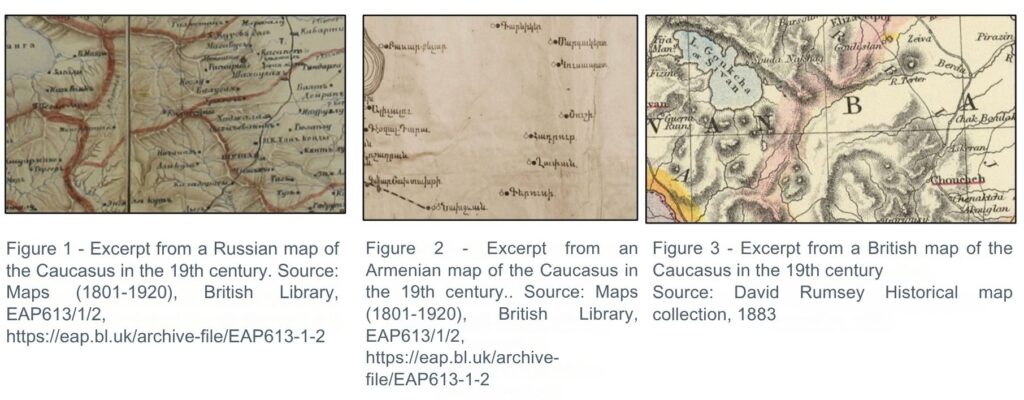

The Caucasus has long been a frontier of empires, and as such, it is shaped not only by typical cross-border dynamics but also by trans-imperial ones. At the village level—the basic unit of daily life—the population may appear homogeneous. But at a regional scale, communities exist side by side rather than together. Each group uses its own language’s place names, and the larger the settlement, the more it becomes a meeting point of communities—and the more names it gathers. Nineteenth-century maps, for example, show routes to “Shushi,” but also to “Shusha.” When foreign mapmakers were involved, yet another variant appears: “Choucheh.”

Even within the same language, multiple names can coexist for a single place, especially in literary texts, where this variety is often used for stylistic effect. One example is Kamer: le petit voyage en Orient1KAPAMAJYAN Simon. Գամեր, փոքրիկ ճամբորդը Արեւելքի մեջ (Kamer: Pokrig djamporte Arevelki metch) [Kamer: The Little Journey to the East]. Constantinople: Tp. Rokos Sakayani. 1911. (285 p)., a textbook used in Armenian schools of the Ottoman Empire to teach reading and geography. In its pages, both “Erzurum” and “Garin” appear—the latter being the name used by local Armenian communities. Modeled on Le Tour de la France par deux enfants, a 1877 textbook by Augustine Fouillée-Tuillerie (writing as G. Bruno), Kamer is a clear example of toponymic coexistence—even in materials intended to educate children about their nation.

The historicisation of borders began in the 1920s and 1930s. At a time when the Soviet authorities were attempting to justify internal administrative borders, they launched a process intended to portray the populations of a given region as direct descendants of earlier inhabitants. This logic led local peoples to ground their territorial claims in historical narratives. Yet this vision stands in sharp contrast to the demographic intermixing that has long shaped the region. While intermarriage was rare, encounters across communities were common. A strategic crossroads, the region has attracted imperial ambitions for centuries. The Treaty of Qasr-i Chirin, signed between the Ottoman and Persian empires on 17 May 1639, ended the series of wars that began with the Battle of Chaldiran on 23 August 1514. During the 16th and early 17th centuries, the area experienced repeated looting and military violence—so much so that Armenian historiography describes the period as a “dark age.” Wartime rapes, common in these conflicts, inevitably contributed to population mixing. The Soviets’ pseudo-scientific vision2BLUM Alain and FILIPPOVA Elena. “Territorialisation de l’ethnicité, ethnicisation du territoire. Le cas du système politique soviétique et russe”. L’espace géographique. 2006-4. (pp. 317-327), marked by the 1930s obsession with ethnic homogeneity, thus contradicts historical reality: as elsewhere, today’s populations are the outcome of centuries of displacement and intermingling.

The naming of places has stirred tensions in the region ever since the collapse of the empires. From the Turkish government’s efforts to Turkify thousands of village names to the institutional renaming that reflects changes in political regimes—such as Alexandropol becoming Leninakan, then Gyumri—toponymy has, since the 20th century, been heavily politicized. This is the subject of Arsène Saparov’s 2022 article3SAPAROV Arsène. “Place-name wars in Karabakh: Russian Imperial maps and political legitimacy in the Caucasus”. Central Asian Survey. Vol. 42. July 2022 (pp. 61-88). Link to the article.. The act of naming has generated an imagined heritage through the designation ‘Western Azerbaijan,’ which functions as a praxeme negating Armenia’s very existence. While this symbolic dimension must be considered by anyone studying the region, it should not obscure a more essential truth: it is the people who inhabit a place—and those who move through it—who give it a name, whether it is a region, town, or village.