Originally published in French on May 6, 2025

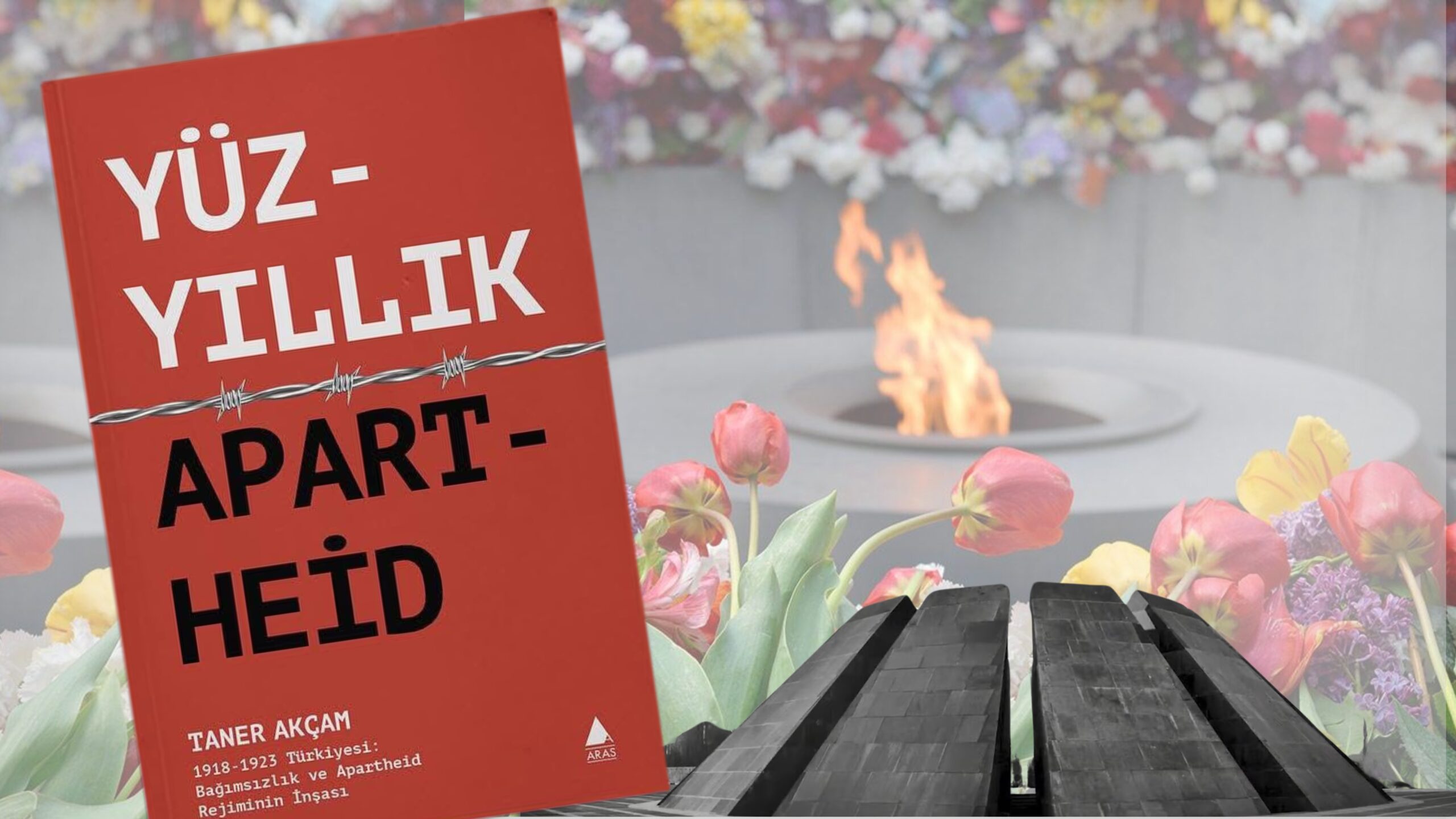

On 25th April 2025, at the American University of Armenia (AUA), Turkish historian Taner Akçam presented the Armenian translation of his book One Hundred Years of Apartheid: A History of the Turkish Republic. A recognised specialist in the Armenian genocide and director of the Armenian genocide research programme at UCLA’s Promise Armenian Institute, Akçam centres his book on a strong thesis: since its foundation, the Turkish Republic has functioned as an apartheid regime: ‘Inequality is not a mere anomaly of this political system, but a founding principle, deeply rooted in the constitution and the legal system’, he explains.

For Taner Akçam, the origins of this system go back directly to the period 1915-1923, marked by the genocide of Armenians perpetrated by the Unionist regime (Union and Progress Committee). In his view, the new Turkish state, founded after the armistice by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, maintained and institutionalised the ethnic hierarchy already in place during the massacres. Sunni Muslims of Turkish origin were placed at the top, Kurds and Alevis occupied an intermediate position, while Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians and Jews were relegated to the status of second-class citizens, true pariahs excluded from political and social life.

To support his assertions, Akçam presents precise and eloquent examples taken directly from official Turkish archives. The 1924 Constitution explicitly defines a Turkish citizen as a ‘Sunni Muslim of the Hanafi school who speaks Turkish’. He also quotes Justice Minister Mahmut Esat Bozkurt, who said publicly in 1930: ‘The masters of this country are the Turks. Those who are not of Turkish origin have only the right to be servants and slaves.”

The historian then reveals the precise mechanisms of this institutional discrimination: from the 1920s, Christians and Jews were registered in special registers called Yabancı Kütüğü (‘Foreigners’ Register”), kept by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, not the Interior. This administrative classification enabled the Turkish authorities to deny them access to senior public, judicial or military posts.

Akçam also refers to a system of ethnic codification, kept secret until 2013: each citizen was identified by a specific number according to his or her ethnic or religious origin – ‘1’ for Greeks, ‘2’ for Armenians, ‘3’ for Jews – thus enabling the administration to discriminate against these individuals, even if the original ethnic identity was not immediately obvious. A striking example cited by Akçam concerns the ban on non-Muslims joining military schools or the security services, a systematic exclusion that remained unchanged for decades.

Professor Akçam compares this situation to that experienced in South Africa under apartheid, and points out that international law categorises apartheid as a crime against humanity, under the 1973 International Convention on Apartheid and the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. He points out that this discriminatory reality remains largely unknown in Turkey, obscured as it is by the official Turkish founding narrative of a ‘glorious war of independence’ against the imperialist powers. This national narrative, he argues, prevents Turkish society from facing up to the real origin of the modern state, which was built on the violent exclusion of Christian populations and ethnic minorities.

In response to a question about the difficulty of moving beyond this dominant narrative, Taner Akçam recalls the ‘1619’ project launched by the New York Times, which aims to rethink the founding of the United States from the arrival of the first African slaves, rather than from the Declaration of Independence of 1776. ‘We need to make the same change of perspective in Turkey: admit that our foundation goes back to the genocide of the Armenians, and not just to the victory over foreign forces’, he explains.

For Akçam, this change of perspective can only come from a profound civic and intellectual movement in Turkey. He refers in particular to the emblematic figure of Hrant Dink, the Armenian journalist murdered in Istanbul in 2007, whom he considers to be the ‘Turkish Martin Luther King’, embodying the hope of a citizen’s mobilisation for historical truth and justice.

During the lecture, the audience questioned the historian at length about the real possibilities for change in Turkey. While Akçam admits that it is difficult to fight against an entrenched official narrative, he nevertheless points to the progress made since his first works in the 1990s: ‘We have won the “psychological” battle. Today, my book in Turkey has gone through four editions in two months. Many conferences are organised online. Civil society has changed profoundly.”

This conference, jointly organised by the AUA’s Masters in International Relations and Diplomacy, the Ex Oriente Union of Armenian Orientalists and Newmag Editions – already responsible for the Armenian translations of Akçam’s previous works (A Shameful Act and Orders to kill) – was a resounding success, with a large audience testifying to the keen interest that this complex historical issue continues to arouse.

By shedding light on these mechanisms of institutional apartheid, Taner Akçam is inviting Turkish society to undertake a profound and necessary introspection: without a genuine examination of national conscience, a genuine democracy will not emerge in Turkey. And on that depends -among other factors- the unblocking of relations with neighbouring Armenia.